Why the Peace Really Failed: The Treaty of Versailles Reexamined

“This is not a peace. It is an armistice for twenty years!” -Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Allied Commander

Anyone with even a basic knowledge of history has heard of the Treaty of Versailles. Somewhat more knowledgeable people will typically, if prompted, recite that the peace agreement humiliated Germany and saddled them with an unpayable war debt, setting up Europe for another World War. And it’s not unreasonable that they say this; it is, after all, the popular historical consensus.

I’m no fan of using AI for research, but in this case, I’ll make an exception, as it’s for a good cause. What better way to objectively determine the broad popular history consensus than simply ask Google’s AI, “Why did the Treaty of Versailles fail?” It answers with a brief paragraph.

The Treaty of Versailles is widely considered a failure because it imposed excessively harsh terms on Germany, including large war reparations, territorial losses, and a "war guilt" clause, which ultimately led to widespread resentment in Germany, creating fertile ground for the rise of extremist ideologies like Nazism and contributing to the outbreak of World War II.

It then cites a lack of German input and the American Senate’s refusal to ratify the treaty as further reasons for failure. All of this matches what I’ve heard in casual conversations and read in my public-school history textbooks: that by being so harsh on Germany, the Entente lit a fire of resentment that would come to burn Europe down two decades later.

This conclusion has never sat right with me, and the rest of this article will challenge it. It will start with some observations about the nature of the treaty and its consequences, then move to thoughts on the Weimar Republic. From there, it will evaluate alternative peace proposals and determine whether they would have done any better.

Vienna without Metternich

When the Paris Peace Conference was convened in January 1919, the great statesmen of the Entente had a gargantuan task ahead of them. The continent was exhausted, and almost every army (except the American army) was either a shadow of its former self, on the verge of mutiny, or both. A Bolshevik revolution had engulfed Russia, and all of Eastern Europe was ablaze from Silesia to Baku. The possibility of a continent-wide communist revolution seemed very real, and there was tremendous pressure from the public to forge a treaty and demobilize the army. The Big Four, made up of Georges Clemenceau (the French Prime Minister), David Lloyd George (the British PM), Vittorio Orlando (the Italian PM), and Woodrow Wilson (the American President), brought different philosophies and agendas to the negotiations, which complicated any consensus. The document they ultimately produced reflected its creation by a fractious committee. It satisfied nobody, but its drafters hoped that was the sign of a fair bargain and not a disaster in the making. They were wrong.

The single largest problem the treaty faced had to have been Wilson and his Fourteen Points, his idealistic program for a peace based on self-determination and a new liberal-internationalist world order. When German Chancellor Prince Maximilian von Baden first requested an armistice in October 1918, it was on the basis of the Fourteen Points. In the subsequent months, the German government was disabused of any notion that the victors intended to implement Wilson’s program evenly, but the civilian population had taken these promises at face value. The treaty’s treatment of Germany, however, clearly violated the principle of self-determination. Sizable ethnic German populations were stranded in Poland, and the loss of Danzig—a 90-percent-German city—stung. Germans also saw their ethnic kin in South Tyrol and the Sudetenland forcibly integrated into victorious states. Most offensive of all, Austria was forbidden by Versailles from joining Germany. To the Germans,[1] they felt the victors had drawn them in with promises of self-determination and plebiscites, only to rob the defeated powers in broad daylight. They felt lied to. They had expected minor territorial losses, but the peace quickly took the character of not merely a defeat but a betrayal.

A 1930 ethnographic map, showing the areas inhabited by ethnic Germans. (While generally accurate, two issues are of particular note. The cartographer considers Alsatians to be German, which is obviously controversial. Additionally, while there were sizable German diaspora populations in the East, this map overstates the areas they constituted a majority.) From the Lange-Diercke Saxon School Atlas, image via Wikimedia Commons.

Germany was not the only nation that walked away feeling betrayed. A fundamental challenge that faced Entente negotiators was the tangle of overlapping promises and ambitions that had accumulated by the end of the war. Some resolved themselves, such as those complicated by Russian claims, which faded due to their civil war and subsequent withdrawal from the conflict. Most, however, remained. The most difficult to address was the fate of the Adriatic coastline, which was disputed between Italy and the Yugoslav-minded Serbia.

Italy had avoided being dragged into war in 1914, abrogating its defensive alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary on the basis that they were the aggressors. Both blocs spent the next months wooing Rome, but ultimately it was the Entente’s promises that won the day. When the war ended, however, Italy’s allies were no longer willing or able to meet their obligations. While Trentino, South Tyrol, and Istria were ceded to Italy, almost all of Dalmatia was granted to Serbia. Again, the principles of self-determination were selectively applied. South Tyrol and the interior of Istria were not ethnically Italian and strongly objected to inclusion in the Italian state. Nevertheless, when the Italians demanded their country be given Dalmatia as agreed, President Wilson rebuffed them on the basis that the territory’s South Slavic population desired inclusion in the new Yugoslav state. The collapse of the Entente’s occupation in Turkey and nationalist revolts in Albania made a bad situation worse. In short order, Italy saw the vast Mediterranean empire it was promised reduced to a handful of border territories. To add insult to injury, Italy was “compensated” for this betrayal with essentially worthless strips of land in the Sahara and in Southern Somalia.

Expected Italian gains under the Pact of London. Image by Smol2204, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In the long term, the consequences of this betrayal were catastrophic. Instead of favoring Italy and ensuring a major European power would be committed to upholding the new order, the British and French propped up a bloated and dysfunctional Yugoslav state.[1] In the process, they created a political pressure cooker in Italy, the explosion of which would propel Mussolini to the premiership. In order to uphold the status quo they had created, Paris found itself consistently forced to support the Yugoslavs against Italy, pushing Rome further into the revisionist[2] anti-French camp. This is how it came to be that one of the victors under Versailles was so disenchanted with the treaty that it joined the vanquished to disrupt the European order.

This all points to the central problem of the treaty: it was not self-reinforcing. A good international system is one in which the major powers, even if not fully satisfied, are reluctant to disrupt the status quo. This can be achieved by an established coalition willing to enforce the order or through a balance of power where any revisions are looked upon with skepticism. So then, what would such a system have looked like? A British-French-American bloc could have secured the treaty. A British-French-Italian bloc could have secured the treaty. A British-French-Polish-Czech bloc, if aggressive enough, might have even been able to secure the treaty. But without the United States, without Italy, and with the Eastern European countries squabbling amongst themselves, London and Paris alone were too weak and too geographically isolated to defend the status quo. Instead, Germany and Italy could, when the time was right, build a revisionist coalition stronger than the defenders of the status quo.

This failure is what made American involvement in Versailles particularly problematic. While Wilson was able to heavily influence the Treaty, he was unable to commit the US to defending the new order it created. The liberal idealism that the Fourteen Points embodied was bold and optimistic, but in practice, it created a European system where the injured nations had the ability to regain their strength and revise it by force.

Between Compiègne and Nuremberg

When German history from 1918 through 1939 is discussed, it is typically split between the Weimar and Nazi eras. In most regards, this is probably the right way to approach it. But in the context of Versailles, it may lead readers to miss the forest for the trees. Contrary to popular perception, Hitler’s moves to undermine Versailles did not represent a clean break from Weimar politics. They were instead an escalation of existing efforts to remove the treaty’s shackles and reassert German power on the European stage. Over the prior decade of parliamentary governments and three subsequent presidential cabinets, the Reich pursued a two-track approach. German governments worked to normalize the Reich’s position on the world stage while quietly undermining nearly every aspect of the treaty, from chemical weapons production to the territorial settlement in the East. This section will demonstrate the depths of anti-treaty sentiment and activity prior to Hitler’s rise, as well as the extent to which it was driven by factors the Entente could not have avoided.

The root of the problem seems to be that neither the German people nor their leaders ever really accepted defeat. Part of this was due to the actions of the Imperial German Army in the closing days of the war. In October 1918, the General Staff informed Chancellor von Baden that the war was lost and he must sue for peace, then turned around and claimed to the people that the army was undefeated in the field. This fed into a delusional attitude on the part of the public that they had not, in fact, lost the war but been betrayed. Some blamed communists and social democrats; others blamed the Jews. But regardless of who was blamed, there was a deep belief that Germany had not been fairly beaten. They cannot be entirely blamed for that feeling, either. On Armistice Day, almost all fighting on the Western Front was occurring in Belgium and France, not Germany. The Soviets had ceded much of Eastern Europe to Germany earlier that year, and German troops were as far east as Rostov and Tbilisi. Then peace was announced, and many Germans expected it to be negotiated between equals, not a surrender. When the terms at Versailles were released to the public, it was a tremendous shock. In their mind, it had come out of nowhere. Thus, we can say that the crux of Germany’s problem was not that it rejected guilt or rejected Versailles but that it simply rejected the defeat itself.

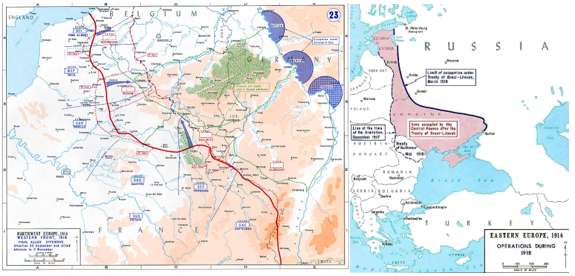

When the war ended, Germany still occupied most of Belgium and a vast territory in Eastern Europe, including the Baltics, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine, and had expeditionary forces in Georgia and Finland. Images: US Military Academy (left); Wikimedia Commons (right).

As a result, the debate was never about whether the treaty should be upheld or not but how Germany could best revise it in her favor. Moderates like longtime foreign minister Gustav Stresemann sought to build a stable relationship with Britain and France to lessen reparations payments and end the occupation of the Rhineland. But even this was pursued with a darker side. The Locarno Treaties helped normalize relations with the Western allies, but by refusing to guarantee Germany’s Eastern borders, Stresemann made sure they also poisoned France’s relationship with the Poles and Czechs. While he understood that Germany could not amend the treaty by force, Streseman sought to diplomatically isolate Poland and bring about territorial concessions by economic means. While moderates played the long diplomatic game, more radical voices on the political right, and especially in the military, looked to war to reverse Versailles.

It was these hardliners in the military that served as the driving force behind the republic’s more tangible treaty violations. When the war ended, the Imperial armed forces were reformed into the Reichswehr, the republic’s new unified military. Its first priority was to secure its position as a state within a state, tolerating parliamentary governance in return for internal autonomy. But the Reichswehr came to see this as a temporary state of affairs, especially after the removal of the relatively nonpartisan General Hans von Seeckt in 1926. His fall was engineered by Colonel Kurt von Schleicher, who represented a faction of younger and highly political officers who saw the military as the only institution that could save Germany. To do so, they proposed turning the Reich into a totalitarian Wehrstaat, or military state. His machinations played a critical role in Hitler’s rise to power, but the victory of the totalitarians within Germany’s military pointed to deeper issues. The Reichswehr had radicalized against parliamentary democracy and was looking for partners to tear it down. If the Nazis were unavailable, men like von Schleicher would have pursued an alliance with other far-right forces to bring about the same outcome.

The Reichswehr’s intent to overturn Versailles can be seen not just in its political schemes but in the covert activity it took. Domestically, army leadership oversaw the creation of the so-called Black Reichswehr, a secret army disguised as labor battalions meant to bypass treaty restrictions. Military and paramilitary officers also led the Fememord, hundreds of extrajudicial killings targeting those they feared would expose their illegal operations. These killings went largely unpunished by the Weimar judiciary, all while men like Carl von Ossietzky, who exposed illegal rearmament, were convicted of treason and imprisoned. The Reichswehr also systematically collaborated with the Soviet Union, a relationship that began already in 1922. This cooperation covered joint chemical weapons production, tank development, artillery manufacturing, and even a flying school, all far from the eyes of the League’s inspectors.

Bearing in mind everything discussed so far, what lessons are to be derived? First, most of Weimar society never truly accepted defeat and intended to restore Germany’s position as a great power. Second, the army and its allies in Weimar society intended to transform the country into a totalitarian regime and wage an aggressive war well before Hitler took power. Between these two facts, we come to realize that the delusions and ambitions within German society meant the Reich would try to challenge Versailles unless the treaty was so lenient it made the vanquished the victor.

Versailles 2.0, 3.0, etc.

The reasons behind the failure of Versailles have been established, but the question of what a successful treaty would have looked like remains open. We have already established that the consensus view in popular history is that the treaty was too harsh. But what would a more lenient treaty have looked like in practical terms? A number of suggestions are thrown about, including some or all of the following.

● Demilitarization of the Rhineland only for a limited time period

● A smaller war reparations demand

● Allowance for Anschluss

● Less harsh restrictions on the military

● Germany to keep Danzig and the Polish corridor

● Some colonies remain German

● Abolishing the War Guilt Clause

The intent of these clauses is to lessen the humiliation the German people suffered in their defeat. Some of these, like removing the war guilt clause, are not unreasonable; forcing that into the treaty did nothing to strengthen the Entente’s position while incensing the Germans. The colonial question, on the other hand, was always of interest primarily to nationalists who would have been revanchist regardless of the treaty’s contents, so it seems doubtful that it would have had much of an impact. Less harsh military restrictions—such as putting a time limit on the Rhineland’s demilitarization and lowering the reparations—could have assuaged German popular anger but would have tangibly increased the Reich’s ability to wage war in the future.

The two clauses that really matter, however, regard Anschluss and the Polish Corridor. Unfortunately, they form a no-win situation. Without conceding on both of these issues, it is unlikely that the treaty could ever have been respected, given the level of delusion at the time on the part of the German public. If the treaty writers did concede on these two issues, they would have put the Reich in a position to dominate Central Europe. Without Danzig, the Poles would have become economically dependent on Germany, binding Warsaw to Berlin’s will. Once Germany annexed Austria, Hungary would have rapidly fallen into the German sphere, and the Czechs, surrounded on all sides, would have been forced to acknowledge German hegemony too. From that position, German power would have radiated out into the Balkans, Low Countries, and Scandinavia, leaving Germany stronger than ever, and thus would have achieved in defeat what it had sought to accomplish through victory.

The unworkability of any such program brings us to a natural conclusion. The fault in Versailles was not its harshness but its leniency. Unless Germany was handed continental hegemony on a silver platter, the Reich, “undefeated on the battlefield,” would inevitably have tried to reverse the treaty as soon as it could. The Treaty of Versailles, we know, wounded Germany’s pride but slowed its return to aggression. An even more lenient treaty would not have mollified the Germans but instead empower them to reassert their power even sooner and with more success. The only way to prevent a resurgent Germany was to remove its material capacity to make war.

The French came to the same conclusion and correctly identified the best means of stripping Germany of its warmaking potential: not simply to occupy the heavily industrialized Rhineland for a time, but to break it off from Germany entirely and establish an independent state under French occupation. Such an action was strongly advocated by French diplomats at Versailles but shut down by united Anglo-American objections. Britain was motivated by balance-of-power considerations and a desire to maintain Germany as a strong trading partner, and Wilson was driven by the Fourteen Points and his idealism. Such a course of action would not have been easy or painless. It’s true that Rhenish separatism was not a majority opinion, but there was a powerful undercurrent of resistance to the Rhine’s domination by Prussian authorities in Berlin. Napoleonic French rule in the Rhineland had left a deep impact, building a sense of unified identity that continued after Prussia annexed the territory. Long before he became the first Chancellor of West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, then mayor of Cologne, tried multiple times to assert the Rhineland’s autonomy, including a 1923 plot hatched with French occupation authorities. In the same year, armed separatists seized government buildings across the Rhineland with French support before Entente authorities lost their nerve and put down the revolt when it turned bloody. Suffice it to say, an independent Rhineland was workable, if France had been allowed to execute it. And the allure of such a proposal was undeniable. If Versailles had broken off the Rhineland and the Ruhr, it could have denied Germany three-quarters of its pre-war coal and steel production. And with French troops on both sides of the Rhine, France would have been in an incredibly strong military position against Germany.

The potential borders of an independent Rhenish Republic. Image from Die Verträge über Besetzung und Räumung des Rheinlandes und die Ordonnanzen der interalliierten Rheinlandoberkommission in Coblenz, Berlin 1925 (Wikimedia Commons).

In addition to the Rhineland, the postwar settlement had one other glaring weakness. Any treaty that fully recognized the threat Germany still posed would have bent over backward to meet Italian expectations. As discussed earlier, the Entente’s broken promises with Rome played an integral role in pushing Italy down a path toward fascism and revisionist expansionism. Yugoslav Serbia was a weak partner, and Italy was indispensable. Yet again, Wilsonian idealism would weaken the Entente’s position in postwar Europe. Granting Italy the territory it had been promised in Dalmatia, supporting its ambitions in Albania, and providing colonial compensation for unfulfilled Ottoman claims could well have avoided a great deal of trouble.

Obviously, all of this is a controversial argument. Most of us will have heard the opposite in school and whenever the road to World War II was discussed. But if you have read this far, perhaps you are willing to consider a different perspective. We have shown how American interference shaped the treaty and how Washington was unwilling to defend the new European order it had so heavily influenced. We have illuminated the depths of delusion the German people retreated into and how the Weimar consensus for peace was a charade. Finally, we have presented the flaws inherent in a more lenient peace, against the backdrop of the well-known historical failures of Versailles. With all of that in mind, there is only one logical conclusion: the popular consensus is wrong. Only a treaty that crushed for good Germany’s ability to wage an aggressive war could have brought lasting peace to Europe and spared it from a far more tumultuous conflict just twenty years later.

Endnotes

[1] This feeling of a bait-and-switch was not felt by the Germans alone. Hungary suffered worst of all, with sizable majority-Hungarian territories lost to Romania and Czechoslovakia in complete contradiction of any principle of self-determination. This ensured that when Germany challenged the European order, it wouldn’t be alone.

[2] Interwar Yugoslav GDP was about 15 percent of Italy’s. Yugoslavia had almost no navy, an outdated air force, and barely any armored force. The German-led invasion in 1941 only took twelve days.

[3] Revisionist: committed to revising the current international order or treaty system.