Global Citizenship Education and the Liberal International Order

Garion Frankel, “Global Citizenship Education and the Liberal International Order,” The Vital Center 2, no. 1 (Winter 2023): 37–46.

(To download the full issue, click here)

By tethering GCE in normative liberal principles that have historically unified and empowered much of the world, scholars and practitioners alike can ensure that their arguments and curricula respectively have a firm, moral basis behind them. Otherwise, GCE’s normative incoherence (along with its political divisiveness) is likely to perpetuate.

Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash.

INTRODUCTION

When the Anglo-American political theorist Thomas Paine famously declared that “the world is my country, to do good my religion,” he could not have possibly imagined that his words would help form the framework behind an enduring multinational program meant to foster peace and harmony between nations. Nevertheless, Paine’s quip has been transformed into Global Citizenship Education, or GCE, a sprawling United Nations (UN)-sponsored pedagogical framework, which, despite only having been named relatively recently, was born out of the rules-based international order that emerged after the Second World War. In the past decade, thousands of schools in the United States, Canada, China, Colombia, and Europe have adopted at least some elements of GCE, which is generally oriented towards equipping students with the necessary tools and knowledge to think and act on a global scale.

It is worth noting that despite the UN’s clarification that GCE “aims to empower learners of all ages to assume active roles, both locally and globally, in building more peaceful, tolerant, inclusive and secure societies,” there is significant debate as to what a genuine GCE entails. Some forms of GCE emphasize skills-based learning, which is designed to foster a globally competitive workforce, while others attempt to inculcate a moral worldview focused on empathy, inclusion, and humanism. A few, less common variants of GCE have an outwardly Marxist or radical orientation, grounded in the works of scholars like Paulo Freire, though it can be argued that these are unorthodox appropriations of GCE rather than a genuine attempt at applying UN tenets. In any case, whether GCE is a mechanism to produce a twenty-first century workforce, a method of producing compassionate, empathetic, and globally-aware students, or a form of Freirean education in which children worldwide are meant to facilitate radical change, the ends are generally the same—GCE means to promote the critical thinking, democratic values, and moral conscientiousness that nominally undergird the liberal international order.[1] This poses an intrinsic problem for GCE advocates, since what is intended to be a global program inevitably becomes subject to national-level considerations.

In response, some scholar-educators have reaffirmed the need for GCE in schools. Elizabeth Barrow at Georgia Southern University argues that GCE should position itself in direct opposition to nationalism, as “promoting empathy for the global village and an understanding of the world’s interconnectedness should be supported by educators across all disciplines and all grade-levels.” Other scholars affirm the adversarial approach, but go a step further, postulating that GCE should be entirely reoriented towards combating populist nationalism. The University of Iowa’s Hyunju Lee, echoing many educational progressives, asserts that nationalism can be useful in creating institutions, but it ought to be tempered by an embrace of diversity and international awareness vis-à-vis public education. Ali Altıkulaç and Alper Yontar’s research suggests that “constructive patriotism,” which they define as the philosophy “sensible citizens” adopt when they embrace democratic ideals, is a necessary condition for effective GCE. These arguments are all hampered by the same concern—they make explicitly normative claims regarding what GCE should do while failing to provide a cohesive framework under which GCE can be successfully integrated.

This poses two problems: First, if education is to be seen as a means to an end, as it is in GCE, then that end must be clearly delineated. Parents and educators alike are highly sensitive to educational jargon, meaning that the lack of a clear goal or outcome can engender hostility and opposition. Second, popular response aside, even if the worldview behind GCE is strong and cogent, the argument for GCE is weaker if it does not have coherent first principles. These notions of right and wrong are critical for obtaining buy-in from diverse and disparate actors. This likely causes the confusion and disparate means-ends theories found in the GCE literature.

Rather than constantly trying to reinvent the wheel, GCE scholars and advocates should consider what made GCE proliferate in the first place. Such a process would inevitably lead back to the two documents that arguably established the liberal international order: the Mont Pelerin Society’s 1947 Statement of Aims, which can be credited with laying the groundwork for contemporary liberal multinationalism, and the UN’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (the Declaration), which postulates that “education […] shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.” That is not to say that scholars are not already integrating these documents into their research. Many have found that GCE and the Declaration have a symbiotic relationship—the Declaration is often cited as being the reason why GCE is necessary, and GCE is often presented as a tool that students can use to understand and evaluate the Declaration.

Nevertheless, these analyses have still not inte-grated the normative bases for these documents. That is what this essay aims to correct. First, I will sketch the historical relationship between the Bretton Woods Statement of Aims, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and GCE. Second, I will argue that GCE’s contemporary normative incoherence is the result of a shift away from its first principles. Finally, I conclude with an assertion that GCE advocates who believe in the UN’s original mission should base their reasoning in liberal multinationalism. GCE’s innate liberalism is not controversial, but its historical and ideological development and normative strength have been understudied and undervalued. The case for GCE is an organically and fundamentally liberal one.

BRETTON WOODS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND GCE

GCE’s innate liberalism is well-known, but scholarship regarding the historical and intellectual processes behind it is not abundant. GCE would not have been possible without the Mont Pelerin Society and UN’s intellectual contributions. They designed the International Monetary Fund to be a liberal institution, and for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to be a liberal document, though one moderated by social democratic ideas. A thorough examination of these contributions and developments is necessary for understanding why GCE has become normatively incoherent, as well as for reinforcing why GCE was initially well-received in the global community.

When the Mont Pelerin Society first met in Switzerland on April 1, 1947, their objective was to cultivate a new order for the postwar world. Their mission was primarily “intellectual” (nominally apolitical) and economic—free enterprise and private property rights were to be maintained at the Soviets’ expense. This new order was to be created through the free exchange of ideas that “contribute to the preservation and improvement of the free society.” Their Statement of Aims, though signed by laissez-faire economists, was not an endorsement of laissez-faire capitalism. Instead, it was meant to encompass both classical and progressive liberalism,[2] unifying the two forces against political oppression.

Despite the Statement’s broadly economic language, the meeting’s attendees knew that they would have to engage in politics sooner rather than later. Indeed, the meeting’s inaugural address acknowledged the “problem” of democracy, noting that the new liberal order was simultaneously threatened by democracy—because voters could choose to annul their own economic rights and therefore deprive the world of the market forces needed for progress and prosperity—and dependent on democracy, because they viewed democracy as a necessary condition for individual liberty. The attendees were also concerned that well-meaning social justice endeavors supported by the general public could disrupt the fragile new system they were in the process of creating. Though perhaps unsettling to modern audiences, this perspective was contextually justified. The Mont Pelerin group was, understandably, terrified of the return of fascism, and there were signs that fascism would, as it had the first time, arrive under the banner of democracy.

The remedy to the extremes of both rank democracy and fascism, to the Mont Pelerin Society, was, in part, education. Though the Society made no comprehensive education policy proposal, its members’ thoughts on education would form the framework for the next half century in educational thought—particularly as it relates to GCE. Frank Knight, a founding Society member, justified education on the grounds that “human nature […] must be molded in the individuals of each incoming generation, to fit the environment […] as inherited from the past; and at the same time, must be equipped to improve it in both sectors.” Later members, like Don Lavoie, would add that “a Humboldtian notion of Bildung [the German self-cultivation tradition] […] is necessary, in his view, because ‘[a] democratic market society requires citizens capable of creative thinking, of working together with fellow citizens, of truly listening to alternative points of view.” While the arguments of Milton Freidman and James Buchanan, disciples of the Mont Pelerin Society, about school vouchers are the best-known of the Society’s educational dialogues, Laovie’s arguments about character education and the philosophy of education remain influential as well. Indeed, Lavoie’s interpretation of Bildung still influences GCE policy in Europe. The UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights built on the Mont Pelerin Society’s conversations. Though the UN’s conversations were mostly directed toward higher education, they were and are still relevant to GCE in light of the credit the Declaration receives for laying the normative and intellectual groundwork for GCE in the first place. All parties to the Declaration knew that the document they were creating, as well as the institutions that would emanate from the document’s implementation, were fundamentally liberal. The document was, in fact, so liberal that many of the more moderate or progressive delegates and scholars were concerned that it would be a radical individualist manifesto rather than a workable statement of liberal principles. Bildung threw a wrench in those plans, since perspectives that were communitarian but still fundamentally liberal insofar as they defended natural equality and individual rights now had to be considered alongside older, individualist doctrines.

As such, the General Assembly, as well as those responsible for revising what would eventually become the Declaration, immediately began grappling with Bildung’s consequences on the relationship between an individual and their community—both local and global. No longer could one merely reaffirm Enlightenment-era individualism exempt from any duties or restrictions without some level of resistance. The opportunities and challenges of a globalized world required a more thorough examination and reevaluation of the individual within it. Adding to the complexity was Bildung’s commitment to a “freedom of science” rather than “academic freedom,” which deeply concerned Anglo-American liberals who were insistent on a continuing need for individual choice and free expression in education.

The final document melded classic and modern understandings of educational rights by first declaring that education is a right. The Declaration acknowledged that “parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children,” but that education ought to be “directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Moreover, the Declaration also made prescriptive arguments about what forms of education governments ought to make available. It demanded free and compulsory elementary education, and prescribed higher and technical education on the basis of merit. These ideas and principles were to be funneled not only through formal classroom instruction, but also through access to and experience with the arts and cultural life.

Initially, liberal ideas were easily found in GCE, and, in some ways, they still proliferate widely. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime still encourages educators to prioritize human rights and the rule of law within GCE efforts in order to “[create] a culture of lawfulness in which citizens understand, participate in defining, and respect laws for the benefit of the whole of society.” In addition, despite the fact that GCE’s recognition of culturally diverse perspectives and traditions can vary widely by the country or educational program, there is still a general consensus that integrating education in cultures other than one’s own into GCE is critically important. Though some leftwing scholars negatively regard the UN’s role in developing GCE standards in line with its own ideologies and goals, these national and international-level institutions are critical in giving GCE programs legitimacy—a prerequisite for educational adequacy in a liberal democracy, much less a country with a nationalist orientation. When the name and weight of a nation-state or a multi-governmental organization is not conferred, it becomes a struggle to implement GCE at all. This has been the case in South Korea, where nongovernmental organizations have struggled to implement GCE due to a perceived lack of normative legitimacy.

In other words, when GCE was first introduced as a concept, it was successful because there were firm moral grounds for its development, and these grounds were fiscally and politically supported by powerful international organizations. But GCE’s popularity is not exclusively or even primarily a function of UN or national government support. World War II had revitalized the public’s faith in liberal and democratic institutions, and there was a movement within educational thought to recenter liberal ideas and principles in the curriculum. The nationalistic enmity stemming from the war itself was transferred to Soviet Communism—a socioeconomic ideology rather than a particular ethnicity or culture. The new commitment to human rights and cultural exchange was built on the “strength of the liberal internationalists’ appeal to liberal ideals, which included an ideological commitment to democratic humanism.” Liberals, particularly those within the UN and the Mont Pelerin Society, made an express commitment to use these principles within national education systems in order to resist Soviet expansion.

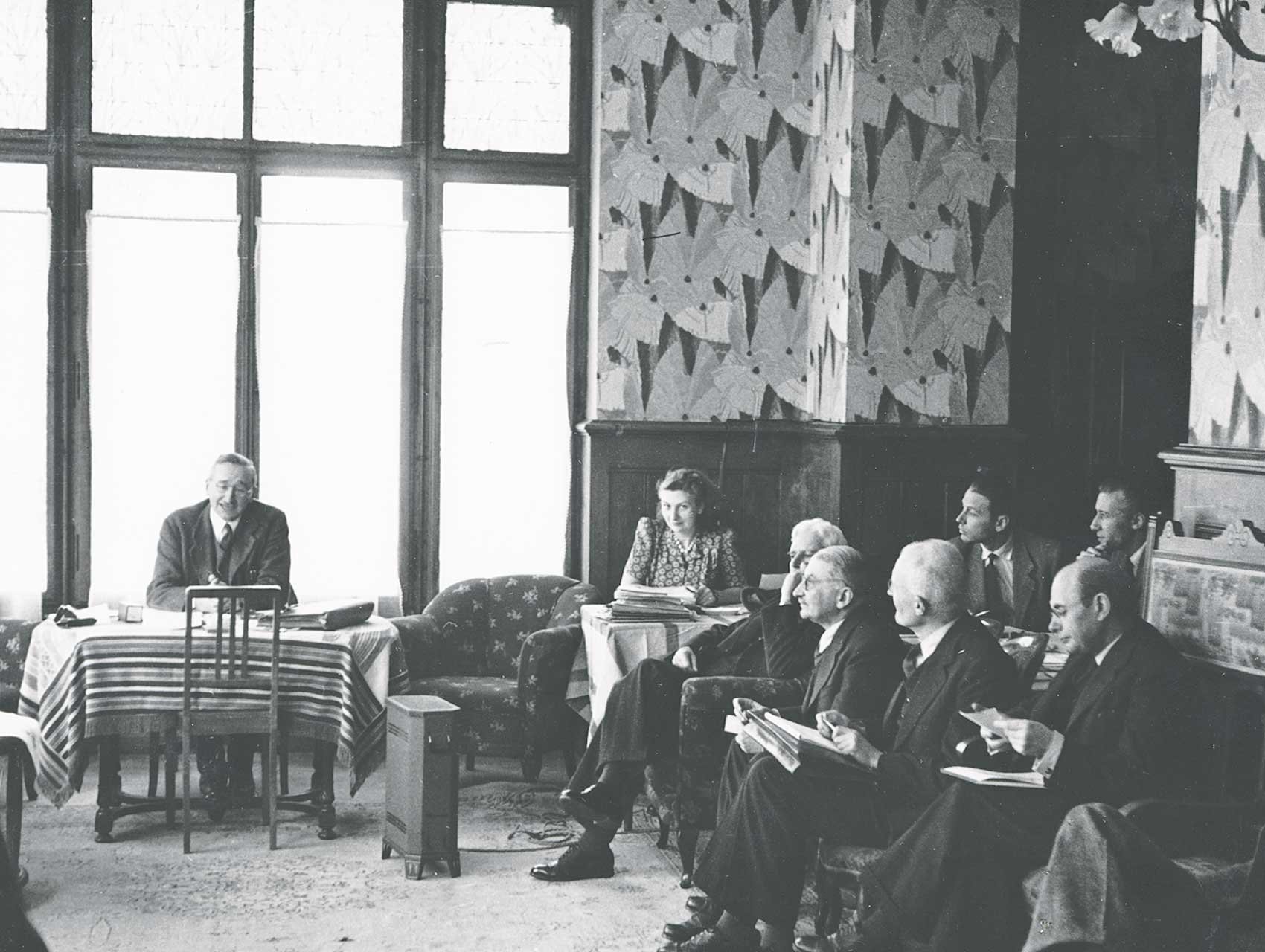

The inaugural meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947. (Photo credit: Hoover Institution Library and Archive)

Ergo, the reason GCE proliferated is because its normative commitments dovetailed with liberal education projects and programs already being developed, including, but not limited to, international schools and international baccalaureate (IB) programs. These programs are also arguably responsible for preserving traditional, liberal GCE within public education. For most students, however, GCE has lost or is beginning to lose the liberal internationalism that made it a compelling pedagogical tool.

GCE’s NORMATIVE PROBLEM

GCE’s normative problem arguably began with Andreotti and De Souza’s landmark edited volume, which features a collection of articles critiquing GCE’s “neoliberal” paradigm from a materialist, postcolonial perspective. Though the scope of the articles included therein varies widely, the core arguments are as follows: first, postcolonial theory is, overall, a useful tool for analyzing GCE’s impact on both education and international relations; second, that GCE is a modern, pacified, but equally destructive form of Eurocentric imperialism, which fails to address the overconsumption and waste that characterize “neoliberal” social structure; and third, that scholars and practitioners alike should look to reframe GCE in a manner that both accounts for and emphasizes non-European traditions and cultures.

Other scholars soon built on these critiques. Some, building on the postcolonial critique of GCE, argued that GCE (even in light of its original mission) should focus on cultivating critical consciousness in young learners. Others viewed the reexamination of GCE as an opportunity to recenter GCE’s pedagogical approach on the pursuit of environmental justice. Others still asserted that “defamiliarization”—the process in which someone views what they have come to see as ordinary through an absurd or unfamiliar lens—could be used to advance a liberationist GCE. What these perspectives have in common is that they are all rooted in the same normative conception of what education ought to accomplish; namely, Paulo Freire’s argument for critical pedagogy. Critical pedagogy was built on a very specific set of social and theological tenets—Freire was a social Christian, and he imposed blame for all social divisions, the distinction between the oppressor and the oppressed, on capitalism. Ergo, the end of pedagogy was to enable individuals, both in their own right and jointly with their community, to remove their bonds of oppression and liberate themselves from the systems and practices that controlled them. Ironically, Freire was also greatly influenced by developmental nationalism. His methods were closely tied to Brazil, particularly his home state of Pernambuco, and it is thereby difficult if not impossible to disentangle critical pedagogy from its roots in Brazilian bourgeois peasant nationalism.

Arguments for natural equality, universal human rights, and the rule of law did not emerge in a vacuum. They are concomitant with a worldview that sees the individual as the basic unit of society, and that the institutions that ought to govern them are fair, just, and somewhat hierarchical. Liberal institutions, justified with normative liberal arguments, are incompatible with normative postcolonial arguments, as liberalism’s innately hierarchical structures are incompatible with those that perceive a fundamental dichotomy between the oppressor and the oppressed. One cannot detach commonly affirmed liberal beliefs—like equality and human rights—from less popular ones—like market economics and Westernization—without accounting for the discrepancy as part of a developed, new normative theory. But the arguments offered by postcolonial scholars of GCE do not meet that bar. They affirm and reject liberal ideas without explanation in the same paragraph or paper.

Indeed, postcolonial critics have applied critical pedagogy to GCE while adopting different or even entirely contradictory normative viewpoints. Waghid and Meta, while advocating for “disrupting individualism”—which they argue would, in accordance with the South African Constitution, expand “the purpose of education beyond serving the market to include serving society by instilling in students a broad sense of values from both the humanities and the sciences”—simultaneously root their ideal GCE in liberal values like human rights, the rule of law, and natural equality. Misiasek commits the same error, attempting to integrate Freirian pedagogy within a worldview that embraces liberal cosmopolitanism. Bosio and Torres, as part of their post-critical construction of GCE meant to end neoliberalism and foster a sense of global citizenship, also endorse many of the normative principles that undergird liberalism—namely, cultural pluralism, universal human rights, and international collaboration. The true normative roots of critical GCE lie in relationships—in the bonds that connect two (or more people) together, but the underlying principles regarding how these bonds came to be and why they should be valued above normative liberalism are almost never explained. The result is that these scholar-activists present as UN-skeptic left-liberals rather than true radicals. Scholars pillory what they decry as “neoliberalism” but then affirm historically and philosophically liberal values and beliefs—terms and the intellectual history behind them are now meaningless.

That is not to say that all arguments critical of GCE have this flaw. Kester, for instance, acknowledges that GCE’s roots are in liberal theory, and suggests a peace education that, while still drawing some of its principles from liberal ideas, firmly rejects liberalism in practice as a system that ferments and allows arbitrary division and Western domination. This “non-dominative” pedagogy is to be rooted in democracy—not just as an institutional arrangement, but in a progressive sense of knowing oneself as an individual and within their community. But the preponderance of critical GCE scholarship makes anti-liberal normative assumptions without grounding them in first principles.

As such, GCE supporters have engaged very little with truly oppositional critiques. Instead, they have tried (unsuccessfully, as I contend) to fold the milder critiques in with the liberal framework that was already present. While the language of the rule of law and universal natural rights was preserved, many liberals recentered GCE’s focus on sustainable development and social justice advocacy. Little normative justification is given for these shifts—only small gestures towards vacuous slogans that are presently politically popular, and vaguely signify discomfort with classical liberalism’s traditional tenets. Insofar as they critique contemporary GCE’s inability to proffer actionable items toward a specific end, critical arguments are rather persuasive.

The Global Citizenship Foundation, while maintaining its desire for a values-based order, argued that Freire’s “pedagogy of hope” should inform and encourage GCE’s pursuit of sustainable development. The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, while nominally liberal and rights-based, has centered its educational paradigm on equity, inclusion, sustainable development, and social justice advocacy. Many activists have also pushed for schools to root GCE in its sustainable development goals rather than the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The United States and Canada have begun to reorient their GCE approaches from values-based nation-centric multi-culturalism to broad youth civic engagement. This shift poses two problems: First, it disrupts GCE’s legitimacy at the practitioner level by failing to empathetically engage with educators. Second, it essentially concedes the normative debate without accounting for GCE’s rich intellectual and theoretical history.

GCE critics often cast modern education as being a new form of imperialism designed to mimic colonization insofar as it cements American political and economic dominance. Education, in this system, others the Global South and consciously attempts to immerse students in Eurocentric epistemology and values. These calls for change and action go almost entirely unnoticed. This is because the idea that “globalisation and hitherto privatisation […] disturb equal public schooling is not accurate historically; it is based on a past that never existed. Today more than ever, dedicated and agentic educators are willing to develop students’ skills and personalities.” Not only are educators willing and able partners in creating a more just world, they are also highly sensitive to how they are treated in the scholarly literature. When educators feel ignored or slighted, they will ignore or even contradict academic scholarship. Since most educators in the developed world favor liberal democracy, the eclectic mix of postcolonialism and left-liberalism has not penetrated classrooms to the degree that scholar-activists would hope.

This state of affairs presents both a problem and promise for GCE advocates. On one hand, by immediately giving way to postcolonial and illiberal critics, GCE advocates, who are still fundamentally liberal, have accepted the critique that liberal institutions and norms are essentially irredeemable. This, from an intellectual standpoint, not only silos GCE from its long and rich theoretical history, built from the Mont Pelerin Society and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but it results in the normative case being weaker. By bending to these attacks, pro-GCE liberals are essentially admitting that liberalism is a coercive and exploitative theory. But the very idea of GCE cannot be separated from liberalism. Without a firm liberal identity, GCE becomes, from a normative perspective, an empty shell. After all, “the primacy of individual rights […] along with the plurality and diversity of ends that people seek in their pursuit of happiness, is a key element of a liberal political order.”

On the other hand, liberals have a distinct opportunity to reclaim GCE and realign its normative liberalism in order to answer modern challenges. At some level, this will involve responding to critical mischaracterizations. A philosophically liberal education, such as GCE, is not, as many on the left would claim, about serving the market. Liberalism merely acknowledges, as political theorists and historians have for thousands of years, that nearly all forms of social organization are going to involve market dynamics. Instead, liberal educators seek to cultivate the virtues that underlie various communities and bring us together as humans under a common paradigm of liberty, autonomy, and respect. Liberals, too, seek to disrupt the exploitation and oppression of the past, and GCE is normatively meant to unite all of humanity under a common, principled banner—not to repeat past cycles of autocracy in the interests of one person or nation. Beyond what a liberal education is meant to do, liberals also have an opportunity to answer critiques related to GCE in and of itself.

A RETURN TO LIBERALISM FOR GCE

Answering these critiques, however, requires recognition that GCE’s liberal origins are not fatally flawed. If anything, liberalism’s shortcomings throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were the fault of liberals rather than liberalism. The postcolonial argument that traditional GCE ignores non-Western traditions and philosophies is thoughtful, nuanced, and well-taken—even if the normative bases for those arguments are suspect. One of the more unfortunate developments within liberalism over the past several decades is its insistence on unnecessarily proving its critics right. Instead of allowing history, context, and institutions (like public education) to assist individuals in pursuing autonomy, justice, and the fulfillment of their obligations towards others, liberalism has become increasingly ontological. In other words, liberals have begun treating the free market as an end in and of itself rather than as a means to an end, or even simply part and parcel of the state of nature. This was never supposed to be GCE’s purpose.

A reinvigorated, openly liberal GCE would unapologetically allow human rights, the rule of law, universal natural equality, and an affinity for pluralism to guide its development and implementation. Indeed, these ideas are not even necessarily Western, as numerous non-Western countries had major roles in the Declaration’s drafting, and these contributions were built on a rich human rights tradition operating outside of Western boundaries. While economic benefits can and do occur as the result of a liberal education, job training should not be the normative focus of a liberal education. This was recognized by the attendees of the initial Mont Pelerin Society who, despite their inclinations towards economics, were firmly committed to societal improvement. Liberals need not (and should not) abandon market economics, but the desire to enable participation in international markets should be tempered by a willingness to facilitate intercultural education and engagement at a community level. Education (particularly cultural literacy programs like GCE) is meant to facilitate an individual’s moral development and autonomy. Moreover, by working with and within established local, national, and international institutions, a liberal GCE can also accomplish the goals many postcolonial GCE scholars put forth—enhancing individual autonomy, creating a space where every person can reflect on their history, identity, and culture, and empowering people to answer injustices around the world.

To that end, proponents of GCE can re-embrace Bildung’s liberating, culturally-aware, and autonomy-focused components, as initially considered by Don Lavoie and the Mont Pelerin Society. Although once a central tenet of politically liberal educational thought, Bildung has frayed to the point where, when it is included in school curricula (which is far from always being the case), it is primarily devoted to discipline and cultural reproduction. A firmly liberal GCE program would integrate non-Western cultural ideas and practices as part of the broader curriculum. Any notion of global citizenship must include the cornucopia of traditions and practices that characterize our world, provided that those traditions facilitate authentic engagement and open communication. Bildung’s emphasis on self-improvement and personal, cultural cultivation would lay a foundation for a world of students who have the knowledge, understanding, ability, and empathy to address global concerns. Reincorporating the Declaration back into GCE programming and teacher training could be the catalyst in promoting this form of intellectual diversity, though additional study would be required to confirm any such suspicions. Regardless, the Declaration provides a clear normative framework for liberals to use when designing and implementing GCE programs. The document may be individualist, but it does not subvert justice concerns in the name of international markets. It is most interested in liberal democracy, pluralism, and awareness of other cultures and experiences.

If liberals, as their normative tenets would dictate, endorse a pluralistic global society, then GCE programs should ensure that they both understand the cultures that pupils are being introduced to and respect the customs and traditions being incorporated. These can include (though are certainly not limited to) introductions to non-Western forms of philosophy and culture, including indigenous and aboriginal history, neo-Confucianism, with its particular emphasis on shared moral knowledge and inherent human dignity, and an embrace of African culture and traditions. Through this process, a liberal GCE would foster respect for different cultures and offer a gentle introduction to a world that has become increasingly interconnected and cosmopolitan. This respect would, in turn, lead to a firm commitment to justice and the pursuit of human rights and liberties for people around the world who, in accordance with a liberal worldview, are unjustly deprived of what is theirs by nature. This commitment can and should be tempered by a given locality’s unique historical and sociological characteristics, but the core skills and principles remain. In any case, any liberal answer to postcolonial critics of GCE would require reforms and im-provements to the contemporary GCE infrastructure.

Some such improvements to GCE can already be seen in higher education. A study of a public administration class at George Washington University, through predicated in many ways on social justice, found that a pluralistic selection of literature increased students’ willingness to discuss controversial subjects, which resulted in broader support for (if not a duty to support) free speech rights as well as increased openness to alternative viewpoints as long as those viewpoints were open to debate, correction, or modification. University experiments in civic engagement and social responsibility projects, mediated by liberalism, have also generated positive results. Though further research is needed to determine whether similar programs would be successful at the PK–12 level, these projects can provide GCE advocates a framework for what liberal GCE programs in the twenty-first century could entail. If nothing else, they are an indication that normative liberalism is capable of using a variety of methods and pedagogical strategies to develop a rigorous and internationally-aware civics and citizenship curriculum.

“Liberals should also do more to assuage concerns that they, and therefore any education system they design, are interested in market systems prior to individual autonomy.”

Liberals should also do more to assuage concerns that they, and therefore any education system they design, are interested in market systems prior to individual autonomy. Indeed, this concern is not new—the debate emerged in the wake of the first Mont Pelerin Society meeting, in which Friedrich Hayek, taking the position that individual autonomy was a prerequisite to a market economy, contested with Walter Euken, who argued that individual freedom is subordinate to the order that a market economy creates. But liberals should champion a GCE situated in liberalism’s true end—an end in which, through education, all people are autonomous, all people have access to justice, and all people have the latitude necessary to develop sophisticated, moderate, and equanimous social attitudes. Any effective, universal response to the global challenges that characterize the modern world will require such forms of respect, and a GCE curriculum that can instill it. This does not prohibit a defense of a market economy—if anything, it encourages it—but it would acknowledge that certain goods within human behavior exist outside the market.

Importantly, “supporting global citizenship doesn’t require a radical shift or transformation of the curriculum. Instead, teachers need to develop an awareness, leadership, humility, enthusiasm, and of course, a willingness to support it.” Minor pedagogical shifts—like implementing digital third spaces, additional experiential learning, and an increased awareness of ethics, political context, and history—would serve a liberal GCE more effectively than rebuilding the institutions and strategies behind the pedagogical approach from the ground up. In any case, GCE programming ought to be crafted and subsequently redirected with a clear end in mind, as GCE is not an end in and of itself. Social justice and sustainable development are worthwhile objectives, but the advocacy surrounding them can be shallow and politically divisive. By tethering GCE in normative liberal principles that have historically unified and empowered much of the world, scholars and practitioners alike can ensure that their arguments and curricula respectively have a firm, moral basis behind them. Otherwise, GCE’s normative incoherence (along with its political divisiveness) is likely to perpetuate.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Andreotti makes a distinction, which has since become commonplace, between “soft” global citizenship, which emphasizes global equality and human development, and “critical” global citizenship, which focuses on overcoming injustice, power imbalances, and restrictions on individual autonomy. I reject this dichotomy, as both classical and progressive liberalism, typically associated with “soft” global citizen-ship, also seek to promote individual autonomy, and rid the world of injustice. The “universalism” Andreotti describes, which they associate with a set notion of how people should live or should be, is instead about principles—beliefs regarding people’s rights, worth, and inherent dignity.

[2] I am making a slight distinction, for brevity, between classical liberalism, which is commonly associated with a historical argument for a market economy and a rights-based philosophy, and progressive liberalism, which accepts many of classical liberalism’s basic tenets, but is additionally concerned with social equality, cultural pluralism, internationalism, and redistribution. The liberalism therein—the belief in human rights, natural equality, inherent human dignity, and the rule of law—is present in both theories and is at the core of arguments favoring GCE. These ideas are hundreds of years old and are at the heart of any contemporary liberal dialogue.